Where Does Your Captive Insurance Premium Really Go?

April 11th, 2024

6 min read

Understanding insurance premiums and where your money goes can be frustrating when it comes to insuring your business, regardless of whether you're in the traditional market or a captive owner. You’re already paying a hefty penny to ensure you have coverage if anything happens, so it’s more than understandable that you want to know exactly where your money is going.

Thankfully, captives are more transparent about where every cent goes and how surplus is distributed after a policy year.

After helping over 130 captive owners, we understand the transparency captives offer businesses, ranging from coverage to profit distribution.

This article will help you understand:

- Where the money goes for your premium

- How the cost of your premium is determined

- Challenges with premium management

- How surplus is distributed after a policy year

- How a captive insurer remains profitable

Read this article, and you'll understand the financial aspect of captive insurers and how they can help your business's bottom line.

Where the money goes for your premium in a captive

When you pay a premium to an insurance company, whether you own it or it is a nationally recognized brand, 40% pays for its operation, and 60% goes toward underwriting profit. Give or take a few percentage points for each.

Paying into a captive is no different, though the expenses tend to be in the mid-low 30% range. They get lower as you get better from having more experience in the captive.

Even as a single-parent captive, your costs should decrease since reinsurance gets a little cheaper. After all, you’re not burning up a bunch of losses.

You’re going to invest the 60% toward your loss fund, which is sitting there and waiting to get paid. It’ll be for your claims, though it will accumulate investment income. The goal of any captive owner (or insurance company) is to maximize the underwriting profit.

Most group captives (all we know of) and some single-parent captives include money in their budget for loss control. This means having a third party or internal people allocated to discuss with you the good, bad, and ugly about your operation with the intent to make it better.

Whatever can be done to minimize claims will help you become a captive owner.

You will also have collateral you need to pay outside of your premium, which is used to pay claims should you run out of money.

If you're wondering how must your business would need to invest to join, try out our pricing calculator.

How the cost of your premium price is determined

A captive will use the claims management of your business as well as actuarial data—high-level math to measure risk and uncertainty—to come up with loss costs. These determine your premium.

This is where some business owners or captive managers can go sideways. Some captive managers get really assertive about what they think the loss cost should be. They’ll tell the actuary to be aggressive on that when underfunding the premium amount that’s needed. By doing this, the business owner is almost guaranteed to cause an assessment on themselves because there isn’t enough money put in to cover claims.

This can happen, especially for smaller businesses with less premium spend. The guy spending $5-10 million on premiums already has a huge loss fund and wiggle room. The same can’t be said for the smaller guys who put in $250,000 on premiums.

A captive that has a long and established history is sometimes easier to deal with since they (typically) have better expenses and can absorb some of that loss with risk sharing. However, the other members may not be happy that they are paying for your losses.

As the business owner has time in the captive, the actuary can weigh the claims history in the captive higher than the outside commercial market. This typically means the insurance renewal premium comes down or stays the same for the business.

It already took a safe business to get into a captive. Being a captive owner is taking that to the next level by becoming better at paying attention and managing their risk.

There’s an old adage: What gets measured gets managed. So, you can generally see the drop in premium upon renewal.

Challenges with premium management?

One of the biggest challenges is having an increasing number of small claims, which we refer to as frequency claims. You’re spending more money to fix the issue in your business and pay the claims.

There are also rare occasions where someone has frequent and more severe claims but refuses to solve the issue. This means you’ll be asked to leave if you’re in a group captive or blow up your single-parent captive.

And your fronting carrier will breathe down your neck because you’re causing them losses. They raise your reinsurance costs, and the actuary also raises your costs. So, if you’re still in a captive, you are almost guaranteed a renewal premium increase.

Whether you’re in a traditional carrier or a captive, having multiple bad years can hit you with premium increases or being kicked to the curb by your carrier.

If you’re a business owner who doesn’t care about the outcomes regarding safety and risk management, captives are not your ideal scenario. The guy who has claim after claim and does nothing about it is the problematic one who is no longer allowed in the captive.

The kicker is that you don’t want to be kicked out of a captive since your collateral will be sitting there for a few years, waiting for the policy years to close. So that money is sitting there and doing nothing. All the while, you need to find insurance somewhere else, which will be more money.

How is surplus distributed after a policy year?

In the insurance industry, you’ll often hear this expression: If you’ve seen one captive, you’ve seen one captive.

Yes, you read that right. All the expression means is that each captive insurer operates differently. This includes surplus distribution.

When it comes to liability lines, there’s a concept called Incurred But Not Reported (IBNR) losses. What needs to be factored in is money held to pay an unanticipated claim at some point after the policy period has ended.

This means the exposure on that policy year extends for many years after.

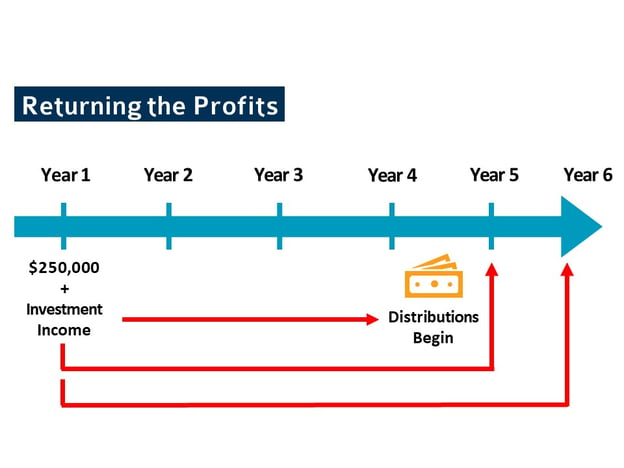

For example, you didn’t incur losses in year one. You likely won’t see a portion of that surplus until year five. You might need that money in year four when you’re hit with a sudden claim.

Note: No matter how robust your safety and risk management programs are, you’ll be hit by a claim at least once every five years. The important thing is to minimize the severity of it.

Continuing with the example, you won’t see a small portion of that year one policy surplus until year four or five. The percentage you’ll see will depend on your captive. You’ll see more of those portions in consecutive years.

Rule of thumb from us: leave the first five years of your profit in the captive. Don’t touch it. Maybe take a letter of credit for collateral. Offset the collateral with the underwriting profit that’s been released to you.

Here’s a figure that can help you understand how the distribution of surplus works over time. It shows how the distribution from policy year one begins at years five and six.

You might get distributions from policy year one in years five, six, seven, and eight, distributions from policy year two in years six, seven, eight, and nine, and so on. Again, the way this happens depends on your captive.

How does a captive insurer remain profitable?

By being efficient. But how do you measure efficiency? How does a captive identify who’s struggling with a member?

One way is being able to look at how frequently a captive owner is having claims come to their doorstep, whether they’re minor or more severe.

Another way of measuring efficiency is looking at the amount being allocated for risk sharing.

For example, if the amount being allocated was at 4% originally and then goes up to 8%, that means the amount being shared has doubled.

When it comes to risk sharing, that means a captive owner has caused a severe loss, resulting in the carrier and other members picking up on the cost of losses.

Remember, being in a captive and managing risk is some pro-level stuff. Captives are full of astute business owners. To notice the line item double means either one or multiple businesses are compromising the efficiency of the captive.

When you see significant increases in your risk-sharing cost, that’s a problem. It means you likely have multiple problematic captive members you’re helping pay for.

Look, we know bad things happen to good people every day. However, if you see this every day and your risk-sharing increases, you’ll be wondering what the deal is and if your captive didn’t allocate enough premium to compensate for this issue.

How can captive insurers help me with cash flow?

Remember, captives are a long-term business strategy that involves putting your money into the right programs and creating more robust safety and risk management programs. When you put in the effort, you’re rewarded for your work. You’re already paying a hefty penny for your insurance premium. You have the right to know where that money goes when you’re a captive member.

To better understand how captives can help with cash flow, you need to read our article Will Captive Insurance Help Me With Cash Flow?

You might be wondering if captive insurers are the right fit for your business. You can take your captive assessment to see if captives are right for you.

Warren, the president and founder of ReNu Insurance, shifted from being a commercial pilot to the insurance industry after 9/11. He applied his aviation safety and risk management skills to insurance, creating ReNu's captive insurance model. This approach cuts costs and turns insurance into a strategic asset. An authority in captive insurance with advanced certifications, Warren drives innovative risk management solutions. Under his leadership, ReNu Insurance sets new standards, offering practical and financially smart risk management. Warren Cleveland, ACI, CIC, AAI